The Significance of Lifelong Learning Culture in Europe

In 2025, the importance of fostering a lifelong learning culture is clearer than ever. Technological change, global challenges, and evolving labour markets demand that people of all ages continuously update their skills and knowledge. Beyond employment, lifelong learning supports active citizenship, personal wellbeing and social inclusion. Families, communities and workplaces all play a crucial role in nurturing this culture, which sees learning not as a one-time phase but as a continuous, life-wide journey.

This makes the insights gained at earlier events still highly relevant today. One such milestone was the European Lifelong Learning Platform’s annual conference on lifelong learning culture, held in Vienna on 5–6 July 2018. The event coincided with the start of the Austrian Presidency of the European Union and Europe’s 2018 Year of Cultural Heritage. Parents International participated actively, bringing the perspective of families and parental engagement to the discussions.

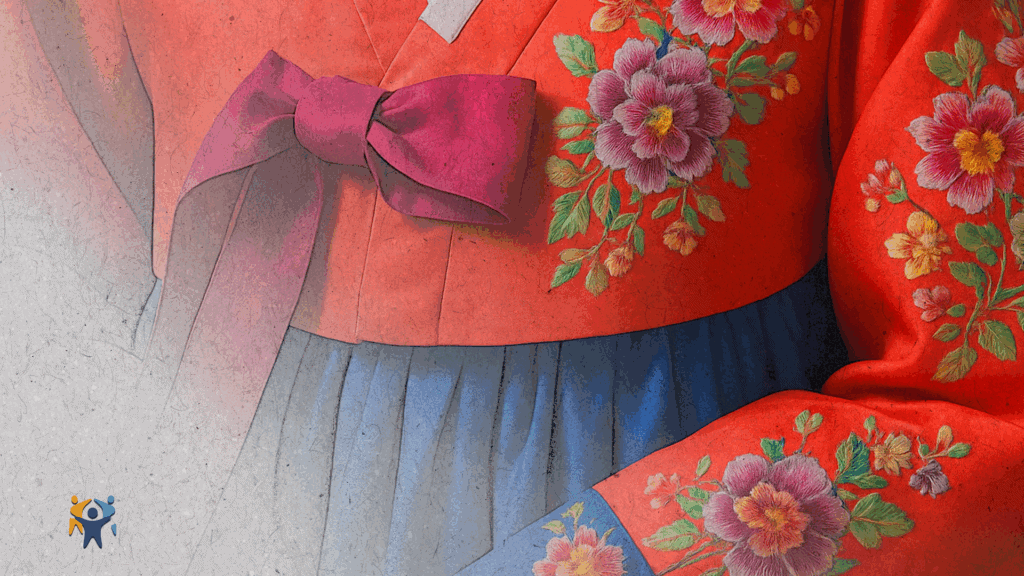

Several speakers inspired participants to explore the links between culture and education and to reflect on both the necessity and the possibility of building a lifelong learning culture in Europe. Among the many contributions, the example of South Korea stood out as a powerful case of transformation: the country evolved into a learning society in just a few decades, despite starting as a largely illiterate nation after the Second World War.

South Korea’s Journey to a Lifelong Learning Culture

The conference opened with policy updates from the European Commission on future education directions and on the Erasmus+ programme. There were also contributions from the outgoing Bulgarian EU Presidency (January–June 2018) and from the Austrian Erasmus+ agency.

For parents, the most significant message came from Denitsa Sacheva, Deputy Minister of Education of Bulgaria. She highlighted the right of migrant children to receive mother-tongue education, even if they spend only a few months in a host country. This is a pressing issue across the globe, but one still often overlooked within the EU’s internal migration context, where public discourse remains heavily influenced by external migration debates.

Professor Shinil Kim’s keynote on South Korea’s experience was particularly compelling. In the late 1940s, 78% of the population was illiterate; by 1965, that figure had dropped to just 5%. Faced with scarce natural resources and deep poverty after separation from North Korea, South Korean leaders decided to build a knowledge-based society as the only viable route to progress.

The result was a full-scale programme reaching beyond schooling. Not only were children enrolled, but adults and early school leavers were engaged through non-formal education delivered by companies, schools, local communities and even the army. This established a foundation where lifelong learning was considered normal and expected.

Today, South Korea offers learning opportunities through universities, specialist centres, civil society organisations, the media and digital platforms. A robust infrastructure supports this approach: lifelong learning institutes at national, regional and local levels, together with stakeholder councils that evaluate policy and monitor implementation.

Validation and certification of learning outcomes are integrated into the system. Learning is no longer seen as linear, beginning in childhood and ending with initial employment, but rather as both lifelong and lifewide—taking place across many life situations.

Professor Kim emphasised that cultural change is necessary not only in schools but also in workplaces, communities and especially within families, in order to become true learning societies. Some European participants appeared surprised at how much of South Korean education is privately financed, a reflection of different cultural and economic traditions. However, the key lesson remains: building a lifelong learning culture is essential for addressing current skills mismatches, a challenge shared across Europe.

The panel discussion raised additional issues relevant to European contexts. Gerhard Bisovsky, from the adult education sector, stressed the importance of long-term programmes rather than short-term projects to ensure sustainability. He also highlighted the need to professionalise all educators—not only formally trained teachers but also parents, who are their children’s most impactful educators. Structured programmes that build parenting skills could be a crucial step toward a stronger lifelong learning culture.

Lifelong Learning Culture in the European Context

Other speakers brought diverse perspectives to the debate. Lars Ebert, representing Culture Action Europe, presented an Erasmus+ project he described as a “glorious failure”, noting the communication gap between academia and artists. This mismatch is familiar to many parents, who often struggle to engage in dialogue with professional educators. Overcoming such barriers is essential for a shared lifelong learning culture.

Ágnes Román, from a teachers’ trade union, observed that schools can no longer be seen as institutions preparing people once and for all for the labour market. Instead, society needs a common understanding of lifelong learning as a mindset. Teachers face significant demands, often working in isolation, and there is little recognition of the equally complex educational responsibilities parents take on—often with no formal training.

Rineke Smilde of Hanze University Groningen discussed the example of musicians, whose “portfolio careers” combine diverse professional activities and require constant skill development. This approach, she argued, represents the future for many professions. Her concept of “biographical learning”—transforming experiences and knowledge across life’s different contexts—reflects the essence of lifelong and lifewide learning. For musicians, portfolio careers require not only technical expertise but also leadership, cooperation, reflection, communication, entrepreneurship and innovation. She also shared examples of music’s positive impact on wellbeing, illustrating how learning can enrich both professional and personal life.

Ulf-Daniel Ehlers of Baden-Württemberg Cooperative State University addressed learning environments for lifelong learning. He argued that while educational institutions have the scientific basis for cultural change, most schools and universities are still far from implementation. As societies shift from lifetime employment to lifetime employability, change is essential.

Higher education, he noted, continues to train students to deliver “safe answers to safe questions”, whereas reality now demands creativity, risk-taking and innovation. Lifelong learning should not only prepare individuals for future success but also serve present-day curiosity and joy. Ehlers called for lifelong learning to become the “master narrative” of education—an idea that resonates strongly with parents, who naturally see learning as a lifelong responsibility and opportunity.

A Shared Vision for Europe

The Vienna conference highlighted how building a lifelong learning culture is both a policy challenge and a cultural transformation. South Korea’s experience shows what is possible when learning becomes a shared national priority. For Europe, the journey involves recognising families, communities and workplaces as key partners, ensuring inclusive opportunities, and promoting continuous personal and professional growth.

By embedding lifelong learning into everyday life—from parenting to employment and cultural engagement—Europe can move closer to a resilient and inclusive future.

More from Parents International

Shift from Projects to Sustainable Programmes

Digital Skills for Parents: Supporting Digital Learning and Inclusion

Inclusive Education: Equitable Access and Inclusion in Education for Every Child in Europe